Intro

In the furious world of tax forms and deadlines – file this by January 31st! submit that by March 31st! and so forth – there’s one particular filing that comes up randomly in conversations and is easy to miss.

That elusive yet highly consequential filing is the Section 83(b) election.

Much like its cousins, this form too is named after the section of the code that mandates it – in this case, Section 83 of the Internal Revenue Code.

What is this fabled Section 83(b) election, when is it triggered, and what bounties and pitfalls does it harbor?

That’s what this post is about.

Let’s dive in.

Meet the 83(b) Election

The Section 83(b) election – or, simply, the 83(b) election – is an election a taxpayer makes with the IRS, opting to be taxed on any income recognized from a property transfer at grant rather than according to the default rule, which taxes income recognized at vest. You have 30 days to file from the day the property is transferred.

The default rule is set by Section 83(a) of the Internal Revenue Code (or, simply, the Code). It stipulates that when qualifying property is transferred, the taxpayer will have to pay tax on the excess of:

- the fair market value of that property when it substantially vests, over

- the amount paid for that property, if any.

The subsequent subsection – you guessed it, Section 83(b) – steps into the scene right after to save the day. It provides an alternative taxation rule; assuming that the taxpayer has made a timely election, the taxpayer will pay tax on the excess of:

- the fair market value of the property when it’s transferred, over

- the amount paid for that property, if any.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

Default rule: taxed upon vest

In December 2024, Jacob is hired at a seed startup as a software engineer. Here’s what his equity package looks like:

- 50,000 shares of restricted stock

- Fair market value (FMV) at grant of $0.01/share – or $500 total

- Four-year vesting schedule, with a one-year cliff

- He doesn’t pay any cash for the equity

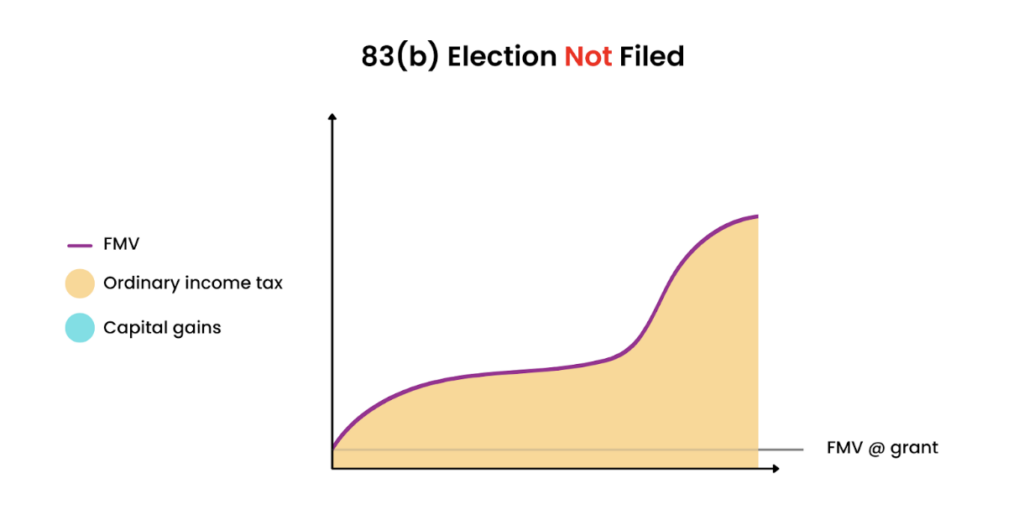

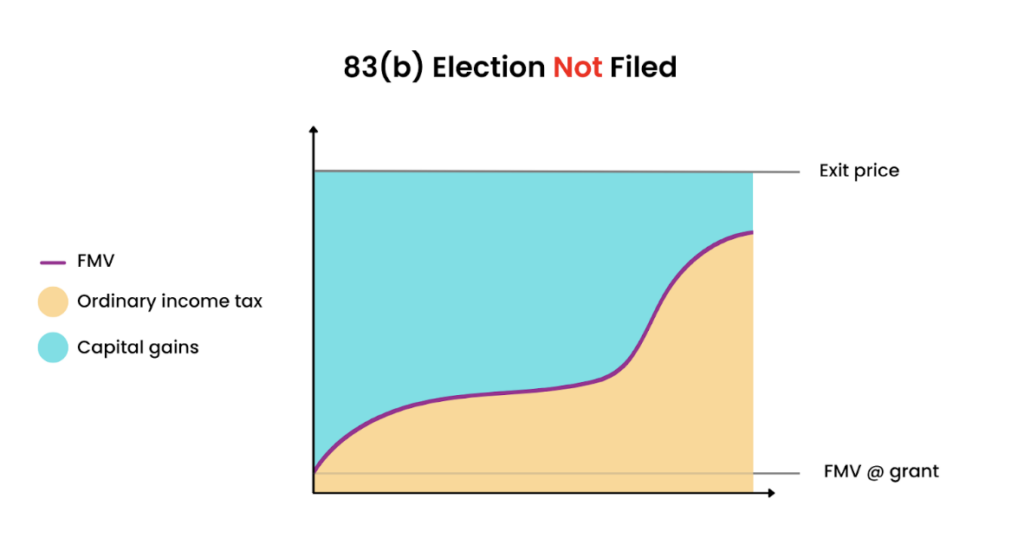

Assuming Jacob doesn’t make a timely 83(b) election and stays on for the full four years, he’ll be taxed on his equity as it vests, at the FMV at which it vests. If the stock were to appreciate over time – which isn’t unusual in an early-stage startup setting, especially if the startup raises a venture round – his ordinary income tax liability would substantially increase.

Simply by way of example, let’s assume Jacob’s startup raises a venture round in 2026, such that the FMV is $2.00/share upon close. A fourth of Jacob’s equity – or 12,500 – will be vesting in 2026, and will be doing so at an FMV of $2.00. As a result, he’ll be recognizing 12,500 x $2.00 = $25,000 of ordinary income attributed to his vested equity that year.

Section 83(b): taxed upon grant

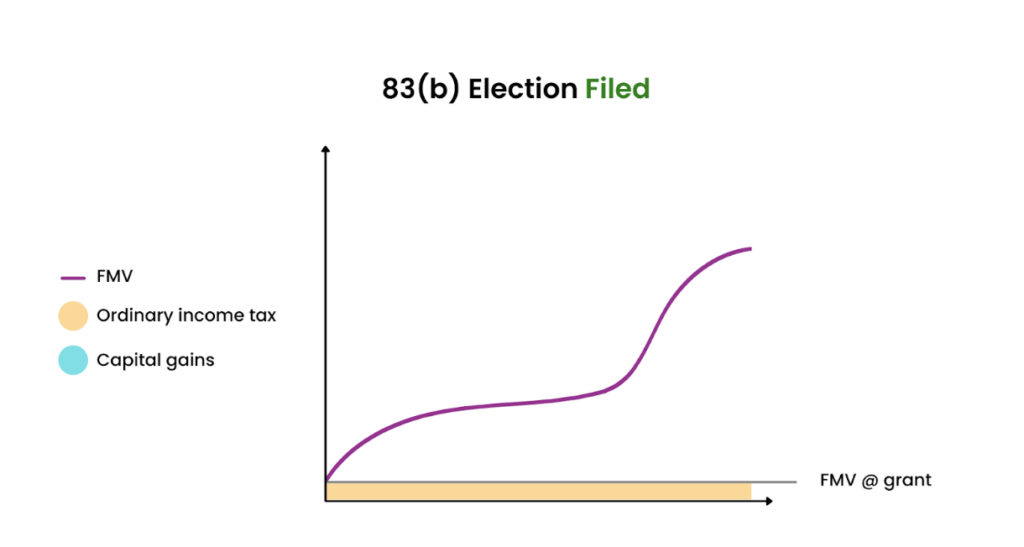

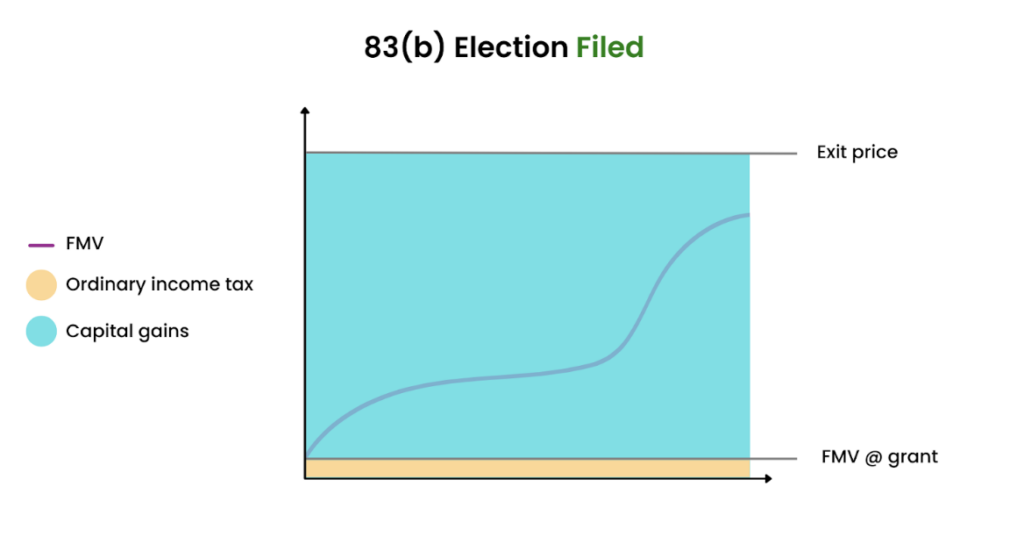

Same scenario as above, except here, Jacob gets in that 83(b) election on time. Here, Jacob will be taxed on his equity at grant, on the spread between the FMV at grant and whatever he paid for the equity (which, in this case, is nothing).

That means he’s recognizing $500 of ordinary income attributable to his entire equity grant. Even if the stock appreciates as it vests, as in the previous scenario, he won’t have to pay any additional ordinary income tax on that appreciation. He’s done.

Ordinary income tax vs. capital gains

Of course, there are two sides to a coin, and there’s no escaping taxes. That stock appreciation that Jacob didn’t pay ordinary income tax on when he filed the 83(b) election – is that just going to slip through the cracks?

Surely not.

If and when Jacob exits his shares, he’ll be liable for capital gains tax on the spread between the exit price and: (a) the FMV at grant, if he filed an 83(b) election, or (b) the FMV at vest, if he did not file an 83(b) election.

When is the 83(b) election available?

The 83(b) election does not apply to just about any transfer of property. To qualify for the Section 83(b) election, there are three main characteristics that the property should hold:

- It should be transferred as compensation for the provision of services,

- It should originally be subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture or not be transferable, and

- It should, in fact, be property.

Compensation for services

The property should have been transferred to an employee or independent contractor (or a beneficiary thereof) in recognition of the performance of services or refraining to perform services. Interestingly, the person performing the services and the person receiving the property need not be the same person.

Substantial risk of forfeiture

What does substantial risk of forfeiture (or SRF) look like? The most common scenario is vesting schedules – a service provider leaves the employ of the company before the vesting schedule has run its course, with the unvested portion of the equity compensation reverting back to the company (usually through a repurchase or forfeited).

In other instances, SRF may take the form of so-called “haircut” provisions, bad leaver repurchase options (at an amount less than FMV), or restrictive covenants.

Property

Property here includes real and personal property, most commonly equity. However, the reason why I stress “property” as a characteristic is because of a common misconception that the 83(b) election is available for any kind of equity compensation.

Here’s a cheat sheet of equity types where the 83(b) election is and is not available. Note that the equity types in the second column are excluded because they aren’t property just yet (at least for purposes of Section 83), but instead are rights toward future property – or are fully vested.

For a more detailed analysis of each of these equity types in relation to the 83(b) election, check out this article.

Seems like filing is a no-brainer?

If only it were that easy. There are some instances where filing is a no-brainer. However, other circumstances require a more nuanced and deliberative approach is warranted. Here are a few factors to be mindful of.

FMV at grant

If the FMV of your stock is super-low at grant, then you’re likely better off filing an 83(b) election. A common example is profits interests, which by definition have an FMV of $0 upon grant. Although entitled to safe harbor treatment under IRS Rev. Proc 93-27 and Rev. Proc. 2001-43, filing a “protective” 83(b) election is usually recommended. The other common example is stock issued in early-stage startups, such as in Jacob’s case.

Fluctuation in FMV

What if your equity vests at a lower value than it had upon grant? In that case, you’d be kicking yourself in the foot had you filed an 83(b) election – had you not, you would be paying tax on a lower FMV. This can be a prominent factor if the FMV at grant is high and/or the company operates in a volatile market.

Start the QSBS clock

In the case of early exercise stock options, actually exercising (and filing an 83(b) election while you’re at it) may make sense because doing so would immediately start the 5-year QSBS period.

Leaving early

When you make an 83(b) election, you’re deciding to pay tax on your entire stock, no matter if it later vests or not. So, if you do end up leaving the company’s employ before your stock has fully vested, not only would you be relinquishing the unvested stock, he would also be foregoing any tax that you had paid for that forfeited equity.

Paying tax on unvested stock

Paying tax on stock can already be an issue because you’re likely paying taxes out of pocket… so, paying tax on unvested stock (which is essentially what you’re doing by making the 83(b) election) is that much more painful: not only you’re paying out of pocket, you’re paying tax on property that you don’t fully own yet.

Conclusion

The Section 83(b) election can be a great tax-saving tool – if you know how and when to use it. While unavailable for stock options (unless early exercised) or RSUs, it’s worth looking into for restricted stock and especially for profits interests. Making the election seems like a no-brainer in some cases, but tread cautiously if the FMV at grant is high or volatile, or you’re unsure if you’ll be around until the equity fully vests. And no matter what, don’t forget: you have only 30 days to file from the grant date.

***

Stepan Khzrtian is the co-founder and CEO of Corpora, which has helped founders and employees file over 2,000 83(b) elections online. Previously, he practiced corporate law for 10+ years, advising hundreds of founders through all stages of the company lifecycle.